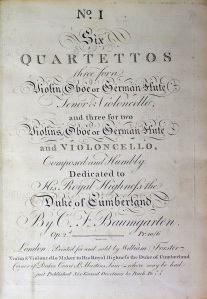

Carl Friedrich Baumgarten (1740-1824) may not be a household name in England these days but in the eighteenth century he was a well-known presence in the drawing rooms of middle and upper-class musical homes. Here at Trinity Laban we hold a set of parts for Baumgarten’s op. 2 quartets for oboe and strings which were written for and performed at private musical gatherings in the home. They have been out of print since their initial publication in 1781 and there are now only a handful of copies in existence.

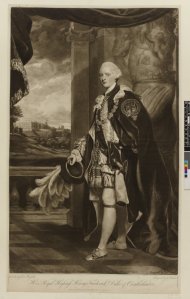

Born in Lübeck, Germany, Baumgarten came to London in his late teens as organist of the Lutheren Chapel in the Savoy and remained in England for the rest of his life. In addition to playing the organ he occupied the position of leader of the orchestra at Covent Garden for many years. However, as a violinist and composer Baumgarten was also in demand in the more private sphere of the domestic music party. Private music parties were a common feature of musical life in England during the eighteenth century. They were a means, not only of entertainment, but also of promoting contacts for musicians and furthering links with patrons.[1]Baumgarten’s most significant patron was Prince Henry, the Duke of Cumberland (one of George III’s younger brothers) who held music parties at his lodge in Windsor Great Park. These parties were described by the oboist William Thomas Parke (1761-1847) who was present during a week-long period of such parties in 1789:

Our mornings were passed ad libitum, and the evenings in executing the fine music of Mr. Baumgarten, which had been composed expressly for the Duke. On one of the evenings the Prince of Wales arrived from Brighton to dinner with his royal uncle. After they had dined we performed some of our usual quartets and quintets; and the Prince being afterwards inclined to sing a part in a glee, he selected the one from the opera of ‘The Flitch of Bacon,’ beginning with the words ‘How shall we mortals spend our hours,’ which was sung by his Royal Highness, Mr. Shield, and me.[2]

Having been published in 1781, Baumgarten’s op. 2 quartets were likely to have been among the ‘usual quartets’ played on this occasion. They were dedicated to the Duke and all contain one part to be played by an oboe or german flute. Given the presence of both the dedicatee and an oboist (William Parke) the quartets would have been an obvious choice.

A few years previously, in 1779, William Parke had proved himself at one of Baumgarten’s own musical parties. These were held occasionally on Sunday evenings and were attended by his friends, apparently as showcases for his compositions. Parke recalled how he fared when asked to stand in for an indisposed clarinettist on his oboe:

Although I had to play a very difficult part in a sestetto at sight, and to transpose it a note lower, I performed my task to the entire satisfaction of the composer and his visitors, amongst whom were Alderman Kirkman, (an amateur oboe player), Sir Thomas Cave, Bart., Mr. Linley, Mr. Sheridan, &c. After supper the company were very entertaining, both ladies and gentlemen contributing to the hilarity of the party according to their respective abilities.[3]

After this event Parke went on to study composition with Baumgarten and in 1783 joined him in the orchestra of Covent Garden as principal oboe. He may well therefore have been the oboist Baumgarten had in mind when he wrote his op. 2 quartets.

Private music parties had much in common with subscription music societies, such as catch and glee clubs, in the eighteenth century. The Chichester catch club, described by the diarist and composer John Marsh (1752-1828), was planned along the following lines:

to meet together for 12 nights on every other Friday […] & amuse ourselves with instrumental music from half past 6 till half past 8, at w’ch time we were to sit down to a supper, consisting only of oysters & Welch rabbits […] & afterwards sing catches, glees, etc. around the fire, whetting our whistles with punch, wine etc. as agreed by the members present.[4]

This description bears a striking similarity to the format of the Duke of Cumberland’s parties with their combination of instrumental music, eating, and part-singing. However, whereas the inclusion of female company and conversation was an important feature of private musical gatherings, the catch club meetings combined music and sociability in an exclusively male, and probably more alcoholic, environment (see our online exhibition Catches and Glees in the Jerwood Library). Other subscription music societies played orchestral rather than chamber music and would include public as well as private evenings, thereby becoming forerunners of the modern orchestral concert.[5]

Baumgarten’s op. 2 quartets have recently been digitized by us in response to an enquiry and copies are available on request for a fee. The Jerwood Library also holds the op. 3 quartets. Both sets are available to study in the library by appointment.

[1] Simon McVeigh, Concert Life in London from Mozart to Haydn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 44-48.

[2] W.T. Parke, Musical Memoirs (London, 1830), pp. 121-122.

[3] Ibid., p. 13.

[4] John Marsh, The Life and Times of a Gentleman Composer, vol. I, rev. ed. (Hillsdale, N.Y.: Pendragon Press, 2011), p. 419.

[5] Stanley Sadie, ‘Concert Life in the Eighteenth Century’, Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 85th Sess., (1958 – 1959), pp. 17-30, (p. 85).